To accomplish a given cellular behavior, CompuCell3D offers many tools, some more suited than others. It is important to understand how these tools are implemented, because each has its pitfalls. For example, don’t try to change individual cell shapes in python — because that part of the software does a poor job of influencing membrane fluctuation; and don’t try to write a c++ plugin to change the cell volume — because it would be redundant and difficult to share.

This post will introduce the theoretical workings of Compucell3D. I hope that it will illuminate how your model works on all levels, and allow you to intelligently choose your tools and programming approach.

I assume you have a moderate understanding of CompuCell already. Perhaps you are an advisor, or an intermediate coder. This tutorial is aimed at those who wish to understand CompuCell more deeply; to understand how the Potts Model resembles (and differs from) actual cellular phenomenon; and to understand the nuances of the different approaches one must take.

Introduction

From their website,

CompuCell3D is an open-source simulation environment for multi-cell, single-cell-based modeling of tissues, organs and organisms…It uses Cellular Potts Model to model cell behavior.

Well, that’s quite to the point. First, lets define the Cellular Potts Model. From wikipedia,

The cellular Potts model is a lattice-based computational modeling method to simulate the collective behavior of cellular structures. Other names for the CPM are extended large-q Potts model and Glazier and Graner model. First developed by James Glazier and François Graner in 1992 as an extension of large-q Potts model simulations of coarsening in metallic grains and soap froths, it has now been used to simulate foam, biological tissues, fluid flow and reaction-advection-diffusion-equations. In the CPM a generalized “cell” is a simply-connected domain of pixels with the same cell id (formerly spin). A generalized cell may be a single soap bubble, an entire biological cell, part of a biological cell, or even a region of fluid.

Better. From this, note how we define a cell: as a collection of pixels. Nothing more, nothing less. Now, let’s break how these concepts apply to CC3D, from the bottom up.

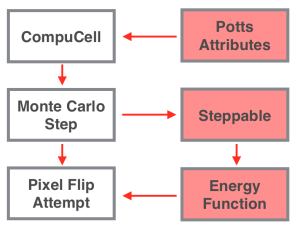

Pixel Flip Attempts

The most fundamental action in CC3D is the pixel flip attempt. Everything in CompuCell — all movement, all changes in cell size and shape — happens on this level. Here, Compucell randomly chooses two adjacent points on the model’s lattice, a ‘change point’ and a ‘flip point.’ These pixels may belong to cells, or they may belong to the medium. Essentially, CC3D asks, “of these two cells — or one cell and the medium — which would prefer to have the pixel at the change point?” If the pixel flip succeeds, then the ownership of the pixel will pass from the cell at the ‘change point’ (or the medium) to the cell at ‘flip point’ (or the medium).

Let’s break this down more rigorously. How does CompuCell know which of these would prefer to have the pixel at the change point? At this point, it accesses all salient properties — such as, what is the cell type and volume? what are the coordinates of the change point? etc — and substitutes this into change energy functions.

These “change energy” functions receive this input and calculates, if the pixel flip succeeds (i.e. if the pixel changes ownership), how exothermic will this be? For a given pixel flip, there will be dozens of such functions operating. For instance, if the “Volume” plugin is activated, it will add a function that checks whether the volume post-pixel flip would be closer to the target volume. If so, that function will return a negative value. (The reader will note, the output of the function is, ultimately, the sum of the exothermicity of the pixel flip with regards to both. And, recall, negative values are energetically favorable.)

When these functions have all run, CompuCell will add them together, giving it a total “changeEnergy.” This process is called the ‘Metropolis algorithm,’ by the way. The pixel flip will succeed if the changeEnergy is negative, and fail if it is positive. You can think of this as a potential energy function.

Typically, these are written in c++ and require you to compile the CompuCell source tree from scratch.

Monte-Carlo Steps

CompuCell3D initiates thousands of Pixel Flip Attempts every Monte-Carlo step (MCS), which you can think of as the unit of time in a CC3D model. Importantly, once per MCS, the software will call upon its steppables. Remember when I said that the energy term queries all salient values during a pixel flip attempt? Steppables determine those values.

Furthermore, steppables are the most easily customized part of CompuCell. They are typically written in Python, which is slower — but often more intuitive and easy to share than the C++ language, which is typically used to write “Change Energy” Functions. (Though you can write steppables in C++ and Change Energy Functions in Python, this is a very specialized task.)

When you see “Energy -xxx” in the console, this refers to the sum of the change energy of each Pixel Flip Attempt within a MCS. Graph this, and you will see the rate at which the simulation assumes a more energetically favorable state.

What this favorable state is, is determined by the parameters of the change energy functions. These parameters come from your steppables.

What this favorable state is, is determined by the parameters of the change energy functions. These parameters come from your steppables.

Model Properties and Plugins

Finally, there are the ‘Potts’ model properties and plugins. These work in a slightly different way from steppables.

Let’s start with the model properties. These determine the basic properties of the model, such as its lattice size and duration. Importantly, here we also specify the ‘temperature’ of the model. This is exactly what it sounds like: the higher the temperature, the more likely more endothermic processes will occur. Practically, the higher this is set, the more the cell membrane fluctuates and seems raggedy.

These are specified in the XML or Main Python File.

Plugins are specified in the same way, which is why I group these, but they are more abstract. A plugin may accomplish one (or more) of four functions:

- It may implement a Change Energy function (e.g. “Volume” or “LengthConstraint”);

- It may be a steppable itself, or do something that resembles a steppable function (“Mitosis”); and/or

- It may keep track of properties of cells, tissues or the simulation as a whole (e.g. “Volume” again).

Because they are so varied, I won’t go into it here. For these, it is better to tinker with built-in plugins to get a sense of their use and variety.

Conclusion

CompuCell has three levels, and each may be used to control your model. Because each level has its focus, they also require different skills. Coding steppables is appropriate for most tasks, but coding an energy function — a much more complicated prospect — may be necessary if built in plugins do not exist. Cell shape, for instance, is very difficult to manipulate within a steppable, but almost trivial to manipulate within a change energy function!

Above all, CompuCell3D and the Potts model is a flexible, powerful suite of tools that will require hours of tinkering to master. Like any scientific instrument, treat it like a puzzle, and your model will show you something unique and thought provoking.

1 Pingback